While the individual items that follow are in no particular order—hence this section bearing the word “Miscellanea”—there is one theme that unites it all. And that is to give you the context surrounding Hayat-e-Saeed as well as a behind-the-scenes look into what is going on into making this translation a reality: This is an ongoing, experimental, and open-ended collection of miscellaneous items aimed at further enlivening this online English translation🌹

- We begin with a meditation on a remark by the biographer—my esteemed maternal aunt, Safia Saeed—who has gifted us with the two-volume biography (in the Urdu language) of Doctor Saeed Ahmad, titled Hayat-e-Saeed, and which is the whole reason for the existence of this website that features its translation (into English.) Coming to the meditation itself, and first to get the full background into the pic above, I invite you to look up the detailed remarks of the biographer: Part of those remarks allude to how “…the completion of this biography took place in the peaceful and spacious residence of my daughter Nasreen [Sadiq] and her husband Waheed [Sadiq], the residence being surrounded by snow-capped mountains in the Canadian city of Calgary…” Well, my cousin Nasreen Sadiq graciously shared a handful of pictures capturing the Calgary outdoors. Of those pictures, two are featured here—this meditation being effectively sandwiched between them.

2. Masha’Allah, the majesty of the Calgary outdoors compels one to slow down and take it all in, slowly, breath-by-breath.

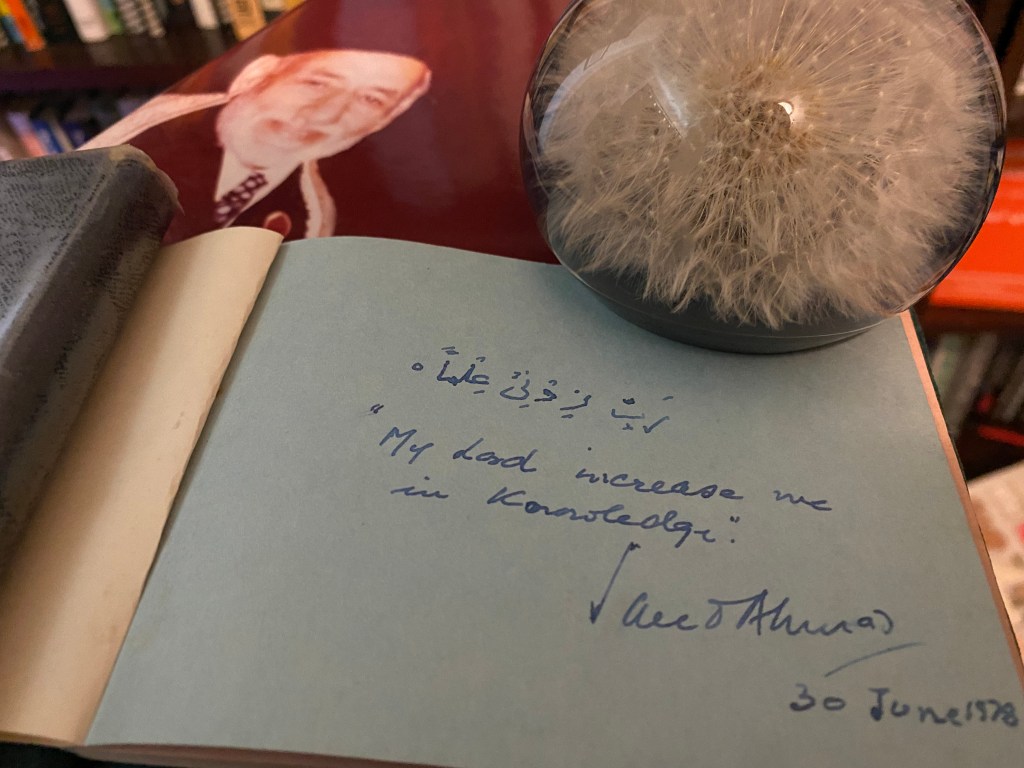

3. Now, the message above is from Doctor Saeed Ahmad himself, being the words which he had inscribed in my boyhood autograph book on June 30, 1978 with his fountain pen. And a gift from his daughter Khadija Begum—my mother—is the paper-weight globe, with a remarkable dandelion specimen encased within, suspended in a state of wonder, and one which you’ll espy in the picture above. The following verses of rhyme come unbidden to mind:

To see a World in a Grain of Sand

And a Heaven in a Wild Flower

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand

And Eternity in an hour

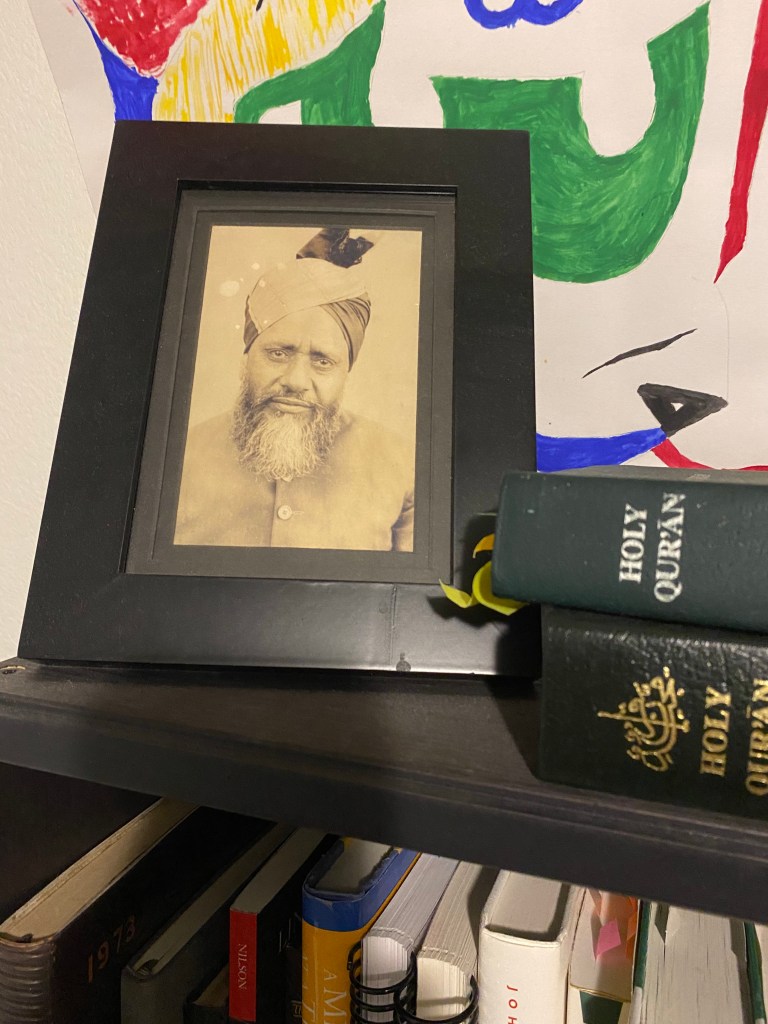

— William Blake (in his poem Auguries of Innocence)

What do you make of those verses?

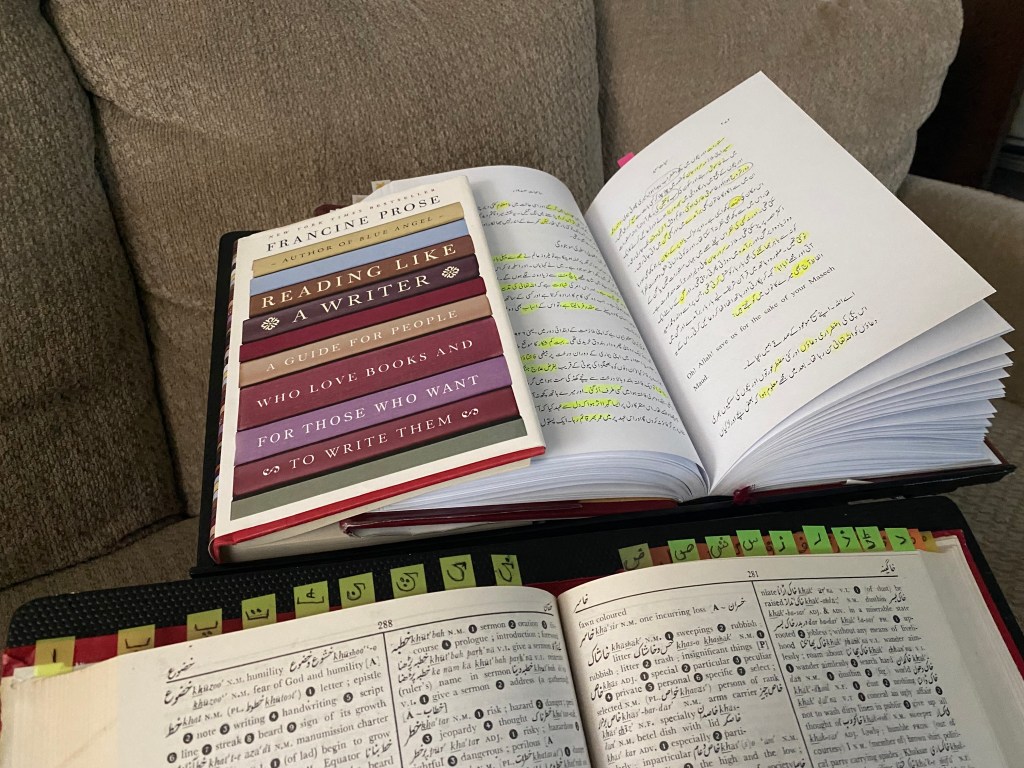

4. Much as food is (usually) prepared in the kitchen, books are (less usually) prepared in libraries. In this case—pictured above are my tools of the trade—I found myself in a public library.

5. Acts of devotion are sublimely satisfying in and of themselves.

6. While that may strike you as rather Zen, there is a method to the madness. Remember the saying that when the student is ready, the teacher appears? Well, I was ready—or at least as ready as I was ever going to be—and then the Urdu-to-English dictionary appeared.

7. Let’s pore over the picture above, with the Urdu-to-English dictionary lit up with tap flags, each of the flags bearing one letter of the Urdu alphabet.

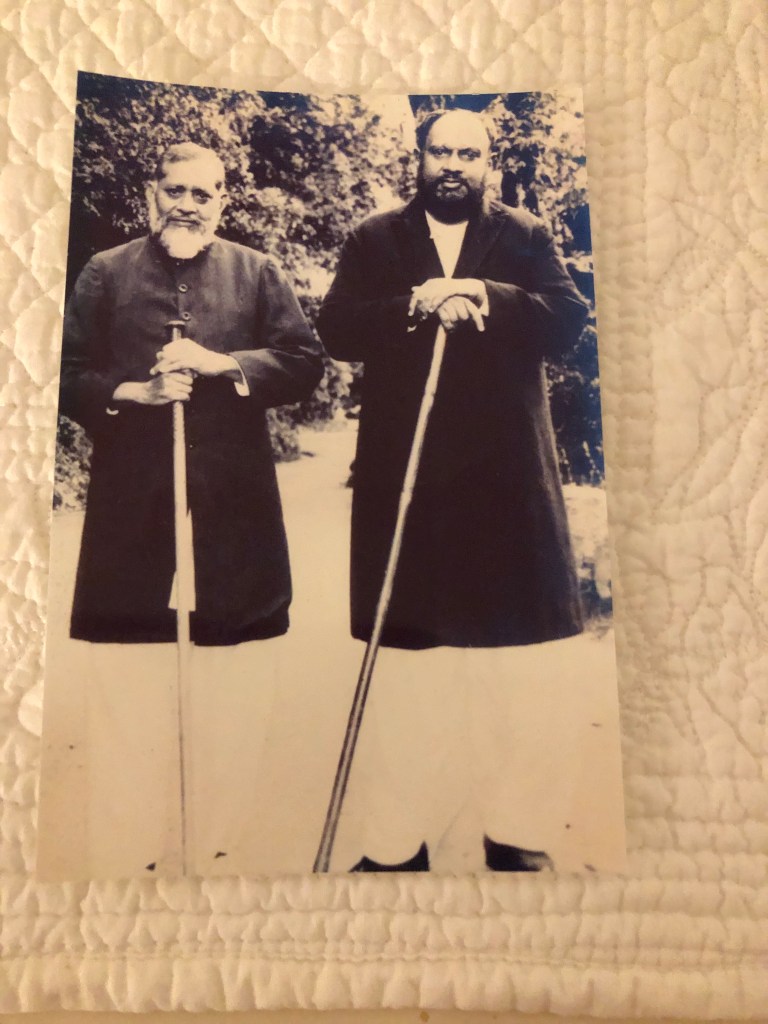

8. A glimpse of spiritual splendor on the face of the founding president of the Ahmadiyya Movement based in Lahore, Pakistan. He was the spiritual father of Doctor Saeed Ahmad.

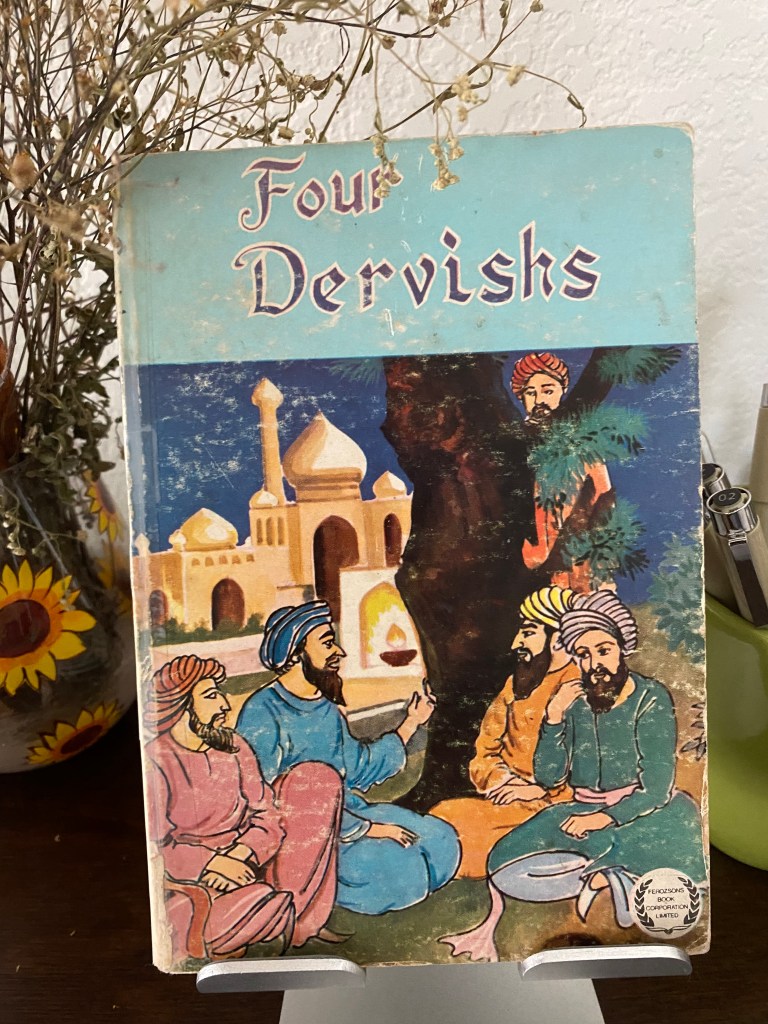

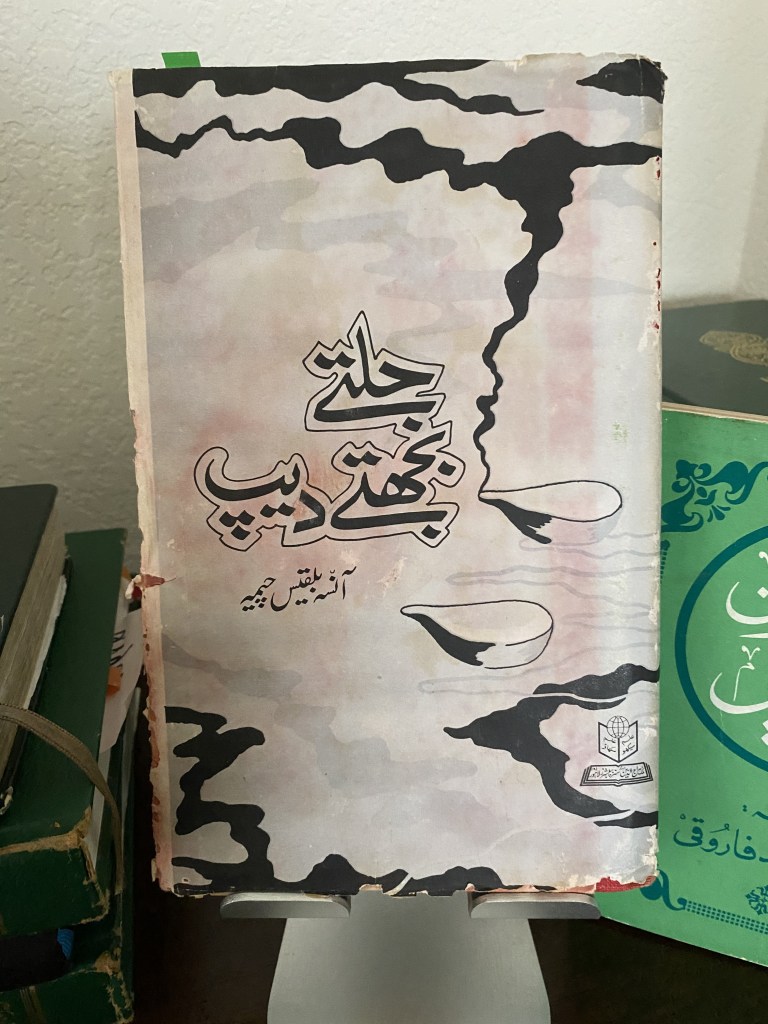

9. Hmm… How, exactly, does one spell the plural of “dervish”? (Check the spellings on the book cover in the picture above, and compare them with mine.) Did I get them right?

10. The “dervishes” book viewed from a distance this time… The same charming appearance, along with an airier view.

11. My mother gave this copy of the book to me, its cover bearing an artist’s drawing of flickering oil lamps.

12. Taking inspiration from the saying that, “What read easy, wrote hard.” (Or at least that’s what I’ve been told.)

13. Let us dwell for a few moments on the couplet—the two verses of rhyme you’ll see boxed in the picture above—in this copy of Durr-e-Sameen, being the collected verses of rhyme by Hazrat Mirza Sahib.

14. Pictured here are my parents: Their spirit and their love permeate the pages of the translation that is featured on this site.

15. The clouds billowing above the hills of Bhugarmang, the sun rays streaming through an opening within their puffy greyness.

16. The biographer—Safia Saeed—graciously shared with me the above as well as the next handful of pictures. She also related how this beautiful cupboard used to be in Doctor Saeed Ahmad’s room in Dadar, and then in Abbottabad (in his room), with neatly-arranged books inside it. He designed this cupboard, and then had it constructed at home by a carpenter.

17. Behold a view of the Dak Bangla, and admire in particular just how well it’s been preserved. Recall, too, that this is where Doctor Saeed Ahmad stayed for a night and then serendipitously discovered the site for what he went on to lead, Masha’Allah, to become the world renowned Dadar Sanatorium.

18. Interior of Doctor Saeed Ahmad’s residence in Dadar. The big change is that the courtyard was cemented over.

19. Around the fountain—now overflowing with the lushness of a variety of native grasses—there used to be a cemented pool of the same shape. In summers, the biographer (my aunt Safia Saeed) further related to me, the household children had a lot of fun, enjoying the sprinkles of water splashing from the fountain. It has been kept neat and clean to this day. On the request of my uncle, Muhammad Saeed, the place was opened for them. There are beds in all three bedrooms, and some utensils in the kitchen. Most likely, it’s currently being used as a guest-house. (Previously, it had been put to use as the residence for an employee of lower grade and had been in rather bad shape.)

20. Pictured above is the exterior view of Doctor Saeed Ahmad’s residence in Dadar. The biographer related to me that the grassy lawns as well as the blooming flowers are all gone.

21. The huge Maple tree was not that huge years ago, the biographer related to me. Sher Zaman Lala’s son narrates that it was planted by her Lalas, a friend of their’s, and by Sher Zaman Lala in the early 1940s. (Sher Zaman Lala was Doctor Saeed Ahmad’s first household cook in Dadar.)

22. Much to be learned from this fine book.

23. So far, I’ve read only portions of this fine book. I’ve heard Doctor Saeed Ahmad praise this book as capturing in a nutshell the background and details of the Ahmadiyya Movement’s history.

24. It’s special. (Please turn to the following picture for details…)

25. That walking stick—the one sitting atop my Urdu-to-English dictionary in the previous item—belonged to Doctor Basharat Ahmad: it’s a prized possession indeed, alhumdulillah.

26. Did you notice how the moon crescent in the distance, picturesquely framed by the arch?

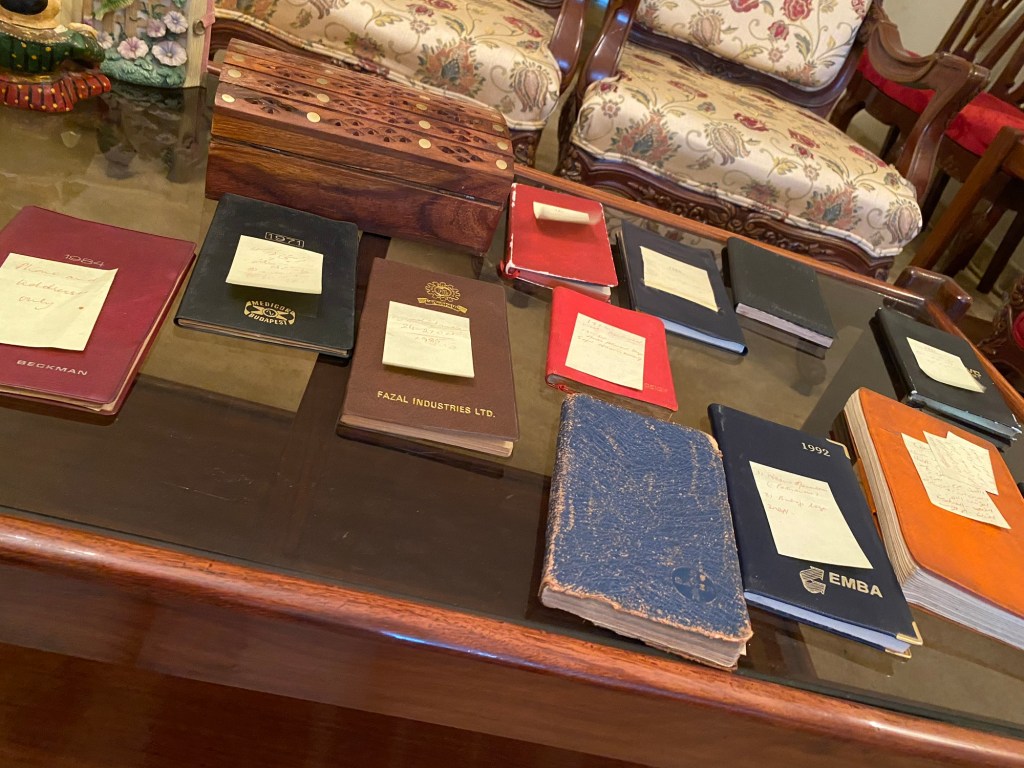

27. Would you like to share what’s atop your bookshelf? (You can do so by posting a comment, perhaps.)

28. An exquisite poem, one whose depth amazed me as I got to grips with the Hindko language in which it is rendered.

29. I enjoyed arranging the books above, and placing them in that particular order.

30. And it is securely placed atop an equally special autograph I got from Doctor Saeed Ahmad, ages ago…

31. We are forever in his spiritual debt for showing us the path forward during a critical juncture in our shared history .

32. Some artifacts related to Maulana Muhammad Ali.

33. Some of the personal diaries of Doctor Saeed Ahmad.

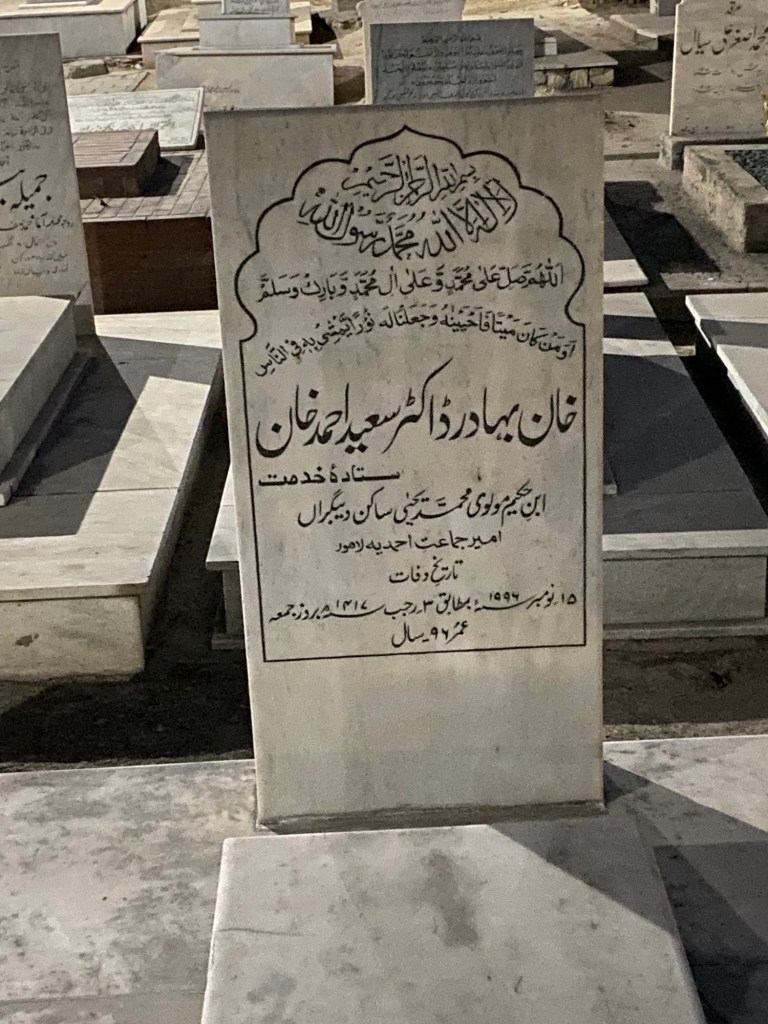

34. The final resting place of Doctor Saeed Ahmad.

35. From afar in a mosque in Istanbul, Turkey, an Arabic phrase which was especially dear to Doctor Saeed Ahmad

36. Pictured above is a painting that exudes elegance, also from afar in Istanbul, Turkey. Rather than (strictly) justify the inclusion of each picture featured here, I’m taking some artistic license in including pictures that were in my mind while translating the biography.

37. Also from afar in Istanbul, Turkey.

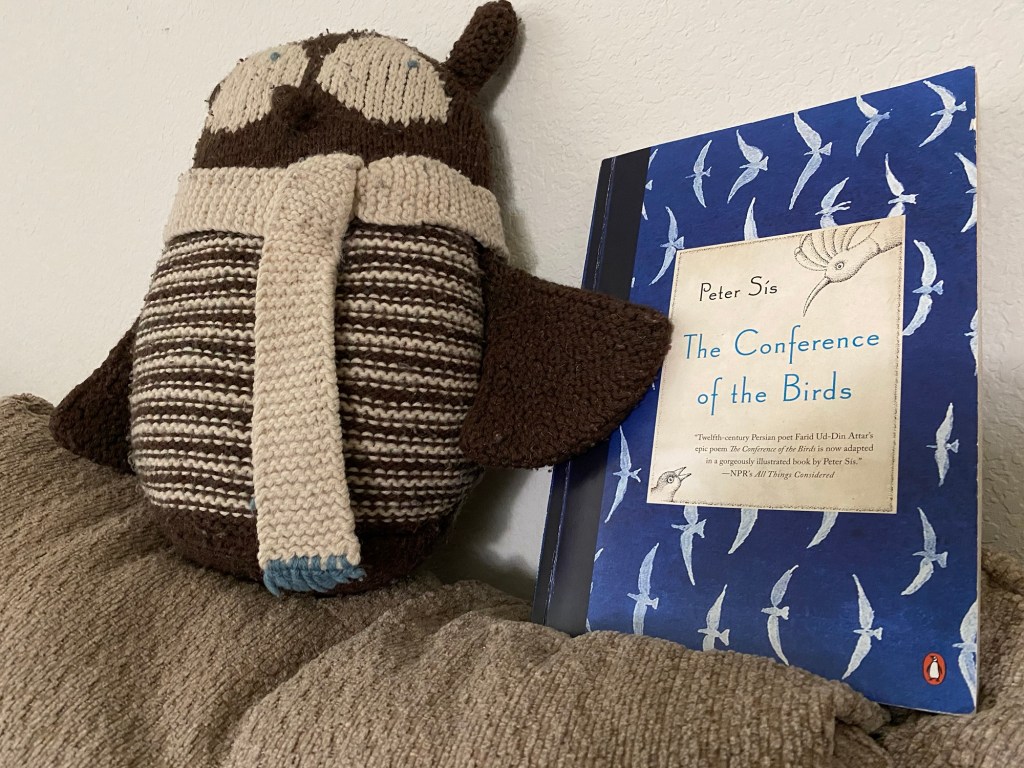

38. And pictured above is a page from the English translation—The Conference of the Birds—being a delightful book by Sufi poet Farid ud-Din Attar, commonly known as Attar of Nishapur. And yes, this one definitely squarely lies in the territory of artistic license.

39. The stuffed owl is making excellent use of its left wing in pointing to The Conference of the Birds.

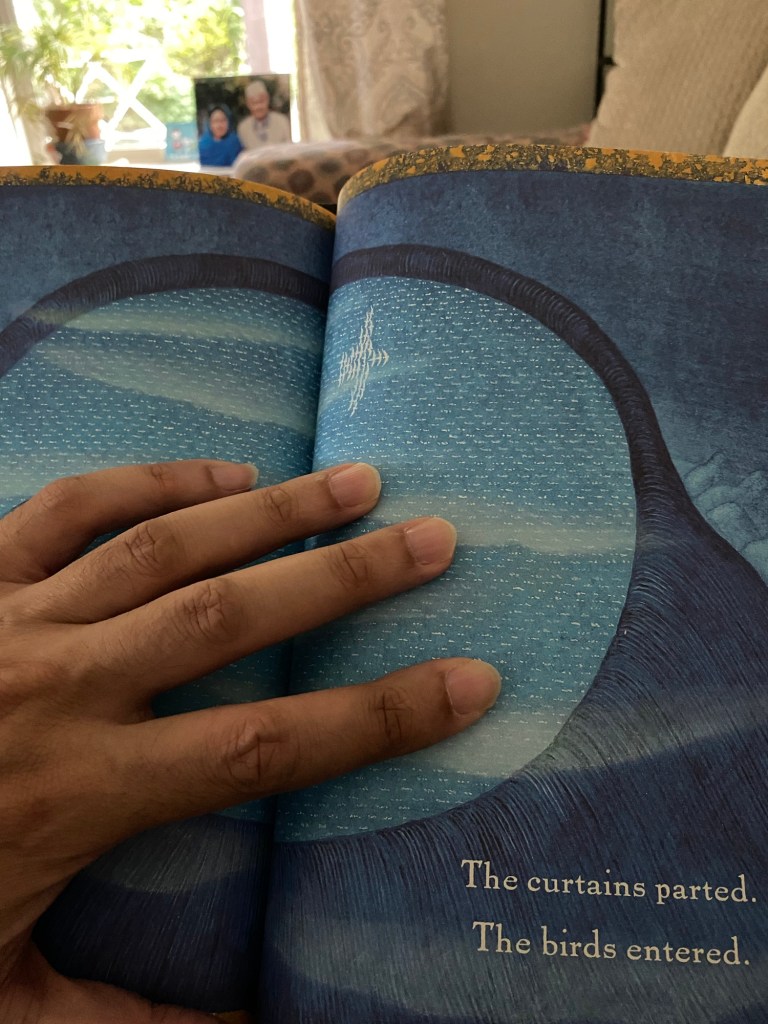

40. Finally, the climax of The Conference of the Birds as reaches its unfolding, or the denouement, as my undergraduate English literature class was fond of pointing out.

41. From afar in Istanbul, Turkey.

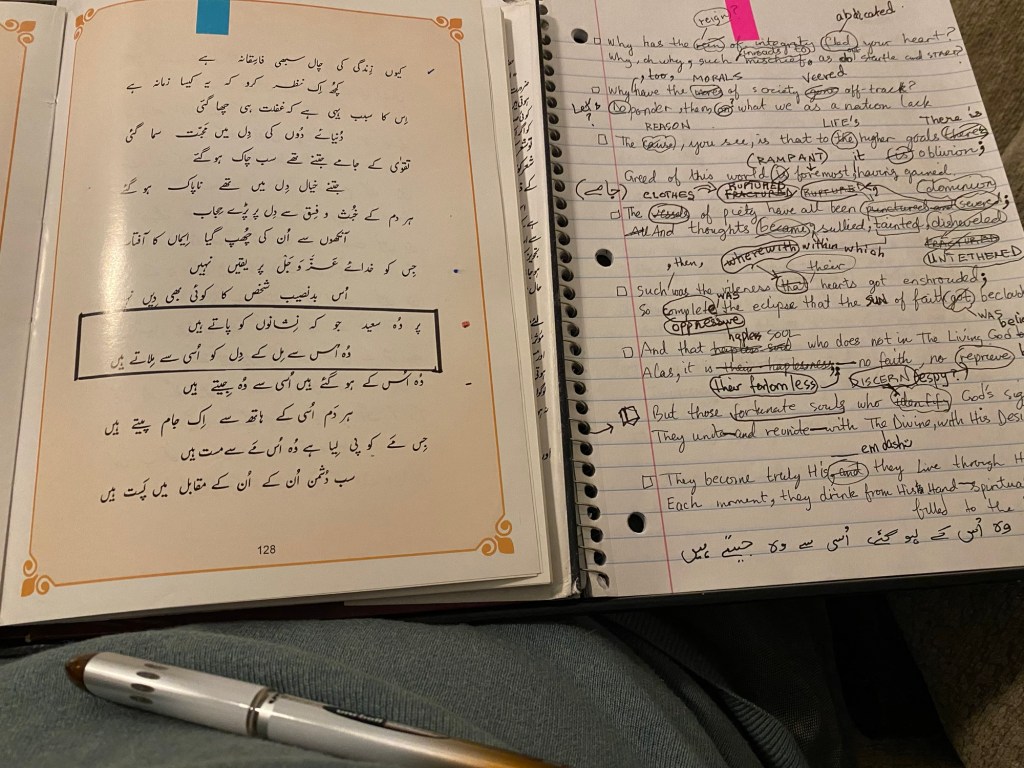

42. One more time, let’s dwell for a few moments on the couplet—the two verses of rhyme you’ll see boxed in the picture above—in this copy of Durr-e-Sameen, being the collected verses of rhyme by Hazrat Mirza Sahib. (Immediately to their right-hand side are my attempts, in longhand, to translate them into English.)

43. What you see above may appear to be a constellation of mere brick and mortar structures, the two dark-brown doors being those of the car garages, and which form a part of Dar-us-Saeed, that being the name of the former residence of Doctor Saeed Ahmad in Abbottabad, Pakistan; and those structures were indeed part of a place and a habitation. But to someone who is familiar with their history, they are more—far more—in that they are steeped in the visceral series of traumatic events that unfolded during the ordeal of June 11, 1974. (The picture above, as well as the numerous ones that follow, are courtesy of my uncle, Ikram Saeed, and for which I’m most grateful.)

44. The gate, past which are located the two garages, Doctor Saeed Ahmad’s car having been hauled out by venomous vandals and set on fire on that fateful day of June 11, 1974. The crowd had then entered the upper level of the house as well as the medical clinic and began their vandalism, setting fire to the rooms.

45. And above you can see featured the nearby region of Dar-us-Saeed, now overgrown by shrubbery.

46. The charred remnants of the medical clinic that was once regularly graced by Doctor Saeed Ahmad as he would go about tending to the medical needs of Abbottabad residents—often without so much as asking for medical fees—some of whom were among those commandeered the setting ablaze of the entire building. (This all took place after the bloodthirsty mob had gained entry, set the car on fire, and looted the house.)

47. The remnants of the chest X-Ray machines, once an integral part of an eminently efficient medical clinic run by Doctor Saeed Ahmad.

48. The picture above shows the lower region of Dar-us-Saeed, the quarters of household employees, plus a view of the adjacent ravine, commonly known in the community as the “khadda”.

49. Another view of the quarters of household employees.

50. And pictured above is a more-aerial view of Dar-us-Saeed.

51. You can see an airy section of Dar-us-Saeed—lined with flower-pots—one just past the gallery passage which, in turn, is behind the main entry to the residence proper. And on that that fateful day of June 11, 1974 it is that the mob of attackers was on the verge of entering the house proper. Just past the aforesaid door is that gallery passage—approximately 14 feet in length—including some limited open space where a decidedly weak and decrepit door is located. And that weak and repaired door was all that stood that traumatic day between the resident of Dar-us-Saeed and the bloodthirsty mob of thousands.

52. And the tranquil scene above is of the Dar-us-Saeed courtyard area.

53. Pictured above is a lovely arrangement of flowers and shrubbery within the Dar-us-Saeed courtyard area.

54. My two cats—one fully alert, the other less so—but both keep guard over my copy of one of the two volumes that make up Hayat-e-Saeed.

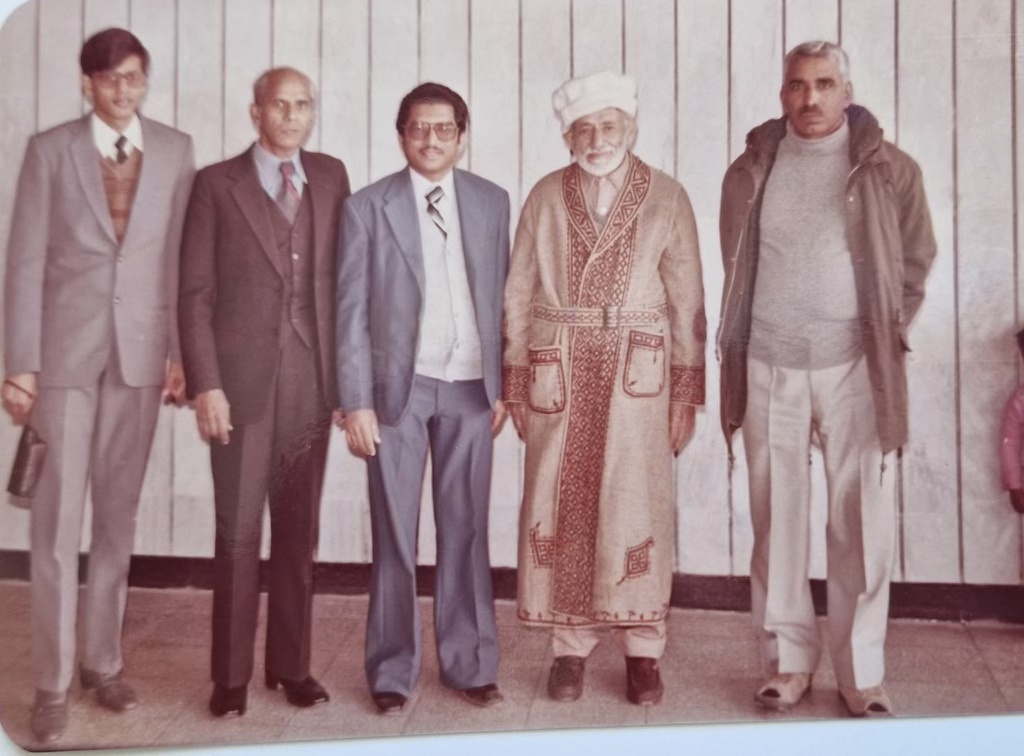

55. Doctor Saeed Ahmad (standing in the front row, third from the right.)

56. Doctor Saeed Ahmad (second from the right.)

57. Pictured above is a note bearing Doctor Saeed Ahmad’s own handwriting—the note appears inside a copy of Hazrat Mirza Sahib’s book titled The Teachings of Islam—and is addressed to his grandson, Mujahid Ahmad Saeed, being a personal note of encouragement on his expressing the intent of computerizing the literature of the Ahmadiyya Movement.

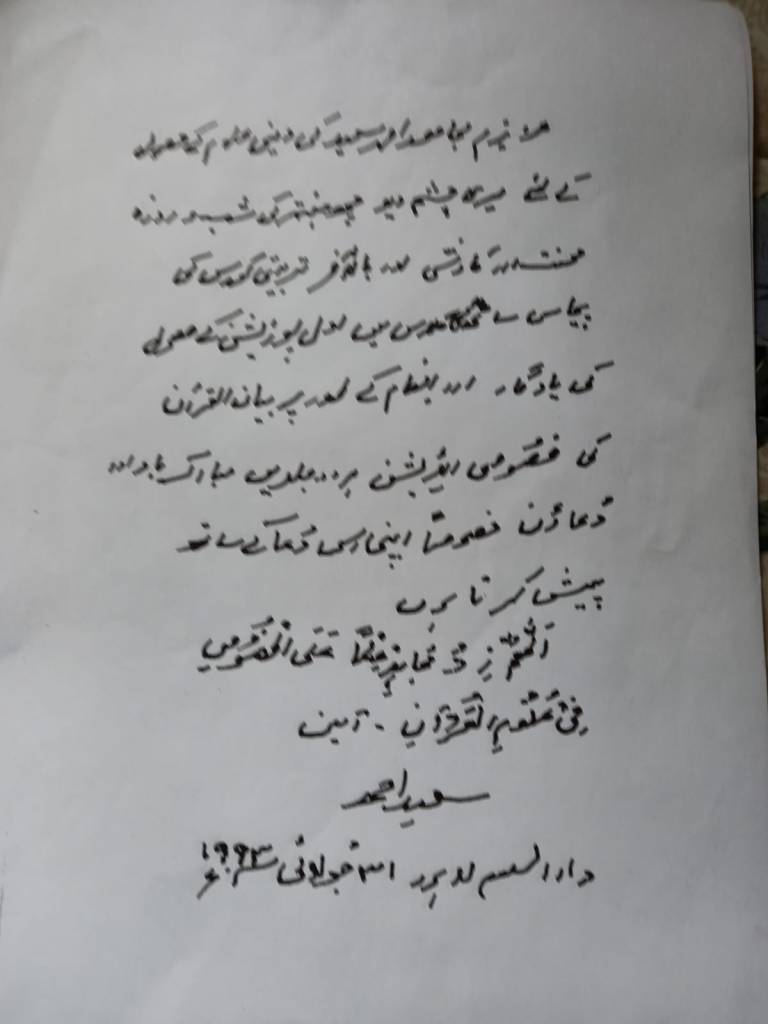

58. And the inscription above—it appears inside a copy of the deluxe edition of Bayan-ul-Quran—also bearing the handwriting of Doctor Saeed Ahmad, and was gifted to his grandson, Mujahid Ahmad Saeed, on securing the first position in annual Tarbiyati (Ahmadiyya Educational) Course.

Leave a reply to Nasreen Sadiq Cancel reply